21st July 2017 Canberra, Australia

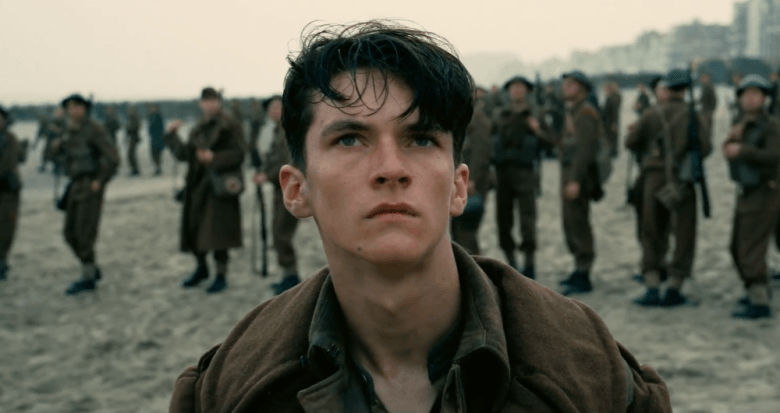

Dunkirk

Last night I was honoured to host a private screening of the critically-acclaimed new blockbuster Dunkirk. The film proved to be a stunning depiction of an iconic moment in British military history. Personally, Christopher Nolan’s gripping account resonated for two powerful reasons.

If you can indulge me I’d like to take you back to 1976.

I vividly remember sitting on my grandfather’s lap in the greenhouse, overlooking his apple trees and a converted Anderson bomb shelter in the garden. We were in the midst of an unforgettable summer; the sunshine never seemed to fade.

We went to my grandparents’ semi-detached house in the north London suburb of Harrow every Sunday morning. Every Sunday I would be given 10 pence to go and buy two war comics, Victor and Warlord. They were the staple Sunday treat for a bespectacled 9 year old rogue who dreamt of cricket and adventure in equal measure.

I knew Grandad had been in the war but – like so many of his colleagues – he never talked about it. The clues were plentiful; a painting of El Alemain, a shell case by the fire, an old Army clasp knife with a tool to remove the stones from horses hooves.

He died a year later. Two decades after that my indefatigable Irish grandmother, Lilian, also passed away. As we cleared the house, one by one we came across medals, firstly threadbare first world war campaign medals and then, curiously untouched in the brown waxed paper they had been sent in, half a dozen from the second world war. Intrigued, my elder brother and I set out to investigate his war record.

Arthur had fought through the first World War and been wounded in the third battle of Ypres. In between the Wars he had worked as a telecommunications engineer for the Post Office and been a reservist in the Territorial Army.

On the declaration of war Arthur had been deployed to Belgium in the British Expeditionary Force. He fought the desperate rearguard action as the Force withdrew across Belgium and into France. His unenviable job was the destruction of the communications infrastructure as the allied troops withdrew.

By the time Arthur reached the beaches of Dunkirk the last of the ships had gone. Arthur was left surrounded by the fast approaching Wehhrmacht.

Waiting at home was Lillian, and her 7 year old and 2 year old boys. Lillian was familiar with tragedy; she had already lost 5 children in childbirth. On the 5th of June the postman delivered the following Telegram “Deeply regret to inform you that your husband Corporal Arthur Alfred Harrison Royal Signals is missing presumed killed on war service. Letter follows”. For six long months Lillian and her children lived under the impression that Arthur had died on the beaches of Dunkirk.

But sometimes there are happy endings.

Six months later, without any warning, Arthur Harrison walked through the front door of the semi-detached in Harrow and embraced his wife and children. After being left stranded, he had hidden with French civilians until the burgeoning Resistance movement had established a trusted network to smuggle him back across the channel. Once there he made his own way back to London and home.

It might be tempting to view Arthur’s tale and the whole Dunkirk experience as a slice of history that has no relevance to contemporary warfare. Who could imagine such a rout nowadays?

Let me fast forward to the turn of the millennium. That nine year old fan of Victor and Warlord had grown up and was commanding a small team in a huge UN mission in Africa. But just like my grandfather 60 years earlier I was running for my life, caught in the cataclysmic maelstrom of a collapsing mission. In my wildest nightmares I couldn’t imagine the chaos that was enveloping the country. Rebel columns were marching through the country massacring and mutilating soldiers and civilians in a drink and drug-fuelled orgy of destruction.

In only two days a force of thousands of troops disintegrated into a totally ineffective, amorphous hotchpotch of terrified, leaderless individuals. All were driven by one panicked aim; to get to the capital and get home. No-one answered the radio, no one issued orders and no-one knew what was going on. The force was in full retreat and being massacred at every turn. Terror was the coin of the day. And it was the most alone I’d ever felt.

Dunkirk provides us a sobering snapshot of war in any age. Despite the comfortable vestiges of political correctness that mask reality in calm days of peace, warfare remains a brutal, visceral, adversarial contest. In war there is exists only victory or death. And in an increasingly dangerous world we remain only one decision away from being cast into an abyss where unimaginable horror becomes the daily norm. As time marches mercifully away from major conflict our collective memory fades; subconsciously we discount the possibility of war.

But we must be the sentinels who guard against blind optimism and complacency. Not only must we be ready to leave the safety and comfort of home to protect all that we hold dear, we must be prepared to speak the unpalatable truth. We need to continue to warn those irrationally hopeful or naïve of the risk and cost of war. Only then will we avoid having to face again what Arthur and his colleagues endured on the beaches of Dunkirk.

With thanks to Roadshow Films for allowing us to screen the film, the National Sound and Film Archive in Canberra for their hospitality, and BAE Systems Australia for their support.