24th January 2017 London, UK

The Holocaust: Why is it still relevant today?

Introduction by Rob Fenn, Head of Human Rights & Democracy Department:

By any standards, 2016 was a dramatic year. Finding myself in interesting times, my personal reaction has been to read history. My phone is now crammed with adventure novels set in an equally tumultuous period for the UK, the mid 17th Century – and in the same location; the streets of Westminster around the FCO. The stories get me through my tube journey and, as I walk up Whitehall, the overlapping of past and present provides a sense of perspective. Yesterday I noticed that a film is coming out about a notorious “Holocaust denier”. I have no idea how good it is. But I enjoyed the idea of setting the record straight. It resonated with the global conversation about whether we live in a “post truth world”, and what that could possibly mean. So it gives me special pleasure to host here a blog by a colleague who lives firmly in the truth-bound world, orientated by values which have been part of British foreign policy for a long time; by scholarship and a strong work ethic. Sue’s work on Holocaust Memorial Day is a credit to this department.

Sue Breeze, Head of Human Rights for a Stable World Team:

For the last five years, I’ve led on the FCO’s post-Holocaust work. This has involved working closely with two different Post-Holocaust Envoys, Sir Andrew Burns, and Sir Eric Pickles. Together we have worked to keep the UK at the forefront of international cooperation to address issues still outstanding, and to promote international collaboration to ensure that the world learns the necessary lessons. This work has made a profound impression on me, which I wanted to share before moving on to my new role in the FCO’s International Counter Extremism Group.

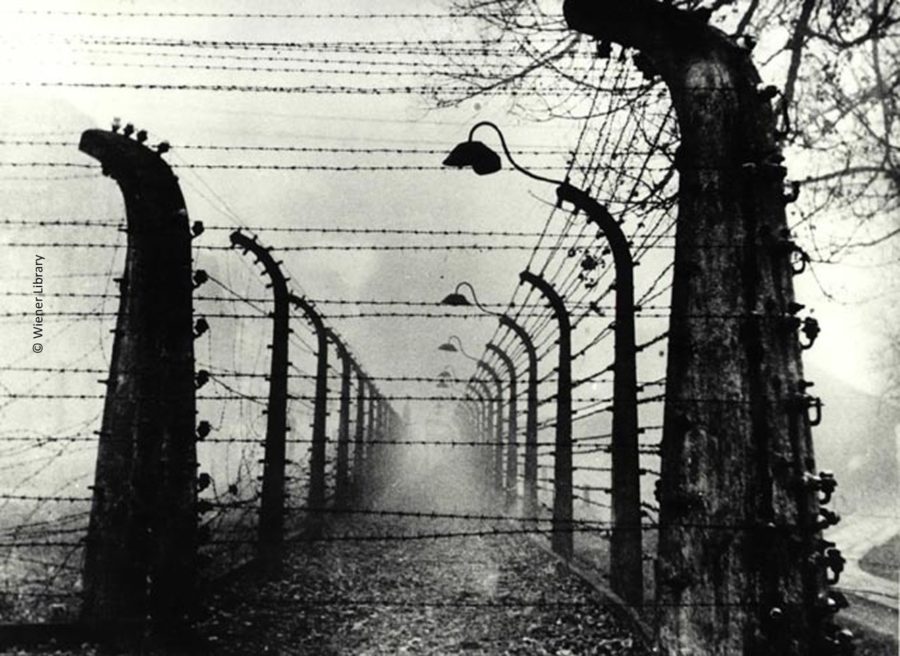

Over 6 million people died during the Holocaust, many of them deliberately murdered in a cruel and calculating way by the Nazi regime and their allies. It was a truly horrific period of history that none of us would ever want to see repeated. Yet, it was brought to an end over 70 years ago. Why then is so much effort still put into commemorating it today, and why does the Government have a Special Envoy on Post-Holocaust Issues?

One reason is that the Holocaust was so traumatic and had such a devastating effect on those who survived that they often tended to push the dreadful memories to the back of their minds as the only way of coping and rebuilding their lives. Only as they approached the end of their life did many of them start to talk about their experiences, often opening up to their grandchildren in a way they had not felt able to do with their children. And with that process came the desire to put right past injustices, for example to ensure that heroes who had saved the lives of others were properly recognised and to recover property that had been stolen from their families. And, of course, to do their utmost to ensure that never again would the world see a regime rise to power and seek to exterminate an entire people group, along with anyone else deemed not to fit their ideal of a perfect society.

Sound familiar? Despite our brave proclamations every year under the slogan “Never again!”, the world has seen subsequent genocides in places like Cambodia, Rwanda, and Srebenica. And doesn’t the Nazi vision sound chillingly similar to Daesh’s hateful ideology too? In the words of George Santayana, “Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it”. So we must keep doing what we can to ensure that we are not those who cannot learn, and to keep the international community vigilant and alert to the warning signs. Our work on genocide prevention through the UN is an important part of this.

But of course there is a limit to what the UN can do. The Nazis’ campaign was so effective and spread so widely because they found plenty of people ready to join them. In many cases these people felt they had no practical alternative and were driven by fear. But deep-seated, centuries-old prejudice across much of Europe against Jews and Roma also created fertile ground for the Nazi ideology to spread.

I find violence deeply disturbing. I never watch horror films, and I switch off those that I find too violent. So I do not enjoy learning about what happened during the Holocaust one little bit. But the fact that it was comparatively recent and happened so close to home, makes the Holocaust a very powerful tool for prompting self-reflection. It jolts us into wondering how on earth people could possibly have gone along with it. And it makes us ask what we would we do in similar circumstances. For me, a good deal of the value in commemorating the Holocaust comes when we look inside ourselves and question our own prejudices. Do we value some people less because they are not like us? Have we swallowed the lie that some people are inferior?

In my work for the FCO I want to help build a better world. I’m so glad that I have a job that enables me to try to do this. It’s what gets me out of bed in the morning. That may sound naive and idealistic, but I believe that if I can help one person to be more open to those who are different to them, then I have taken a step towards my goal. Remembering the Holocaust and other genocides, learning their lessons and seeking to right their wrongs is a powerful way of doing just that. As I move to a new job, helping to counter extremism internationally, I look forward to exploring how tackling prejudice, both conscious and unconscious, can help to build societies that are more resilient against extremism.