11th January 2012 Ottawa, Canada

The War of 1812

As we approach the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812, Canadians have begun to reflect on its role in shaping what Canada is today. But this is also a chance for Britain to consider its own contribution to the conflict, and how its relationship with Canada has evolved over the past two centuries.

The War of 1812 came at an interesting time in North America’s history. It was the second war between Britain and the United States. The first was essentially a civil conflict within British North America; while the second, 1812-14, involved the US as an independent state. Given this context, the War of 1812 was significant in Canada’s history for two reasons. First, it helped give the people of what was to become Canada a sense of identity, a recognition that while they were inhabitants of North America they were politically distinct from their American neighbours. Second, despite decades of recurrent tensions, not least over borders, the war was the last armed conflict between Canada-Britain and the US. Though not necessarily foreseen, what followed was 200 years of peace and increasing prosperity between Canada, Britain and the United States. This second point is fundamental. This peace was to lead not only to the largest cross-border trading relationship in history, between Canada and the US; but to a lasting three-way political, economic and cultural partnership, which was twice to become a critical military alliance, as we all fought side by side during two world wars.

In many ways, 1812 was a defining moment for a fledgling Canada, which was to go on to become a confederation from coast to coast, then The Great Dominion, and ultimately an independent state (recognised in law by the Statute of Westminster in 1931, the 80th anniversary of which Canada has just quietly commemorated. It must be the most understated transition to complete political autonomy in history). But in 1812, it was still British North America, and Britain would defend it. Local Canadian militia, and allies among the native peoples, were absolutely essential to this, but 5,000 British troops and support from the Royal Navy led in large part to their success. The United States was not yet the military power it is today. Nevertheless, they had a preponderance of local force. But they suffered from a lack of able commanders, and never sufficiently concentrated their efforts. British forces benefited initially from the experience and competence of professional soldiers like General Brock. Despite repeated US incursions, they were always able to repel boarders.

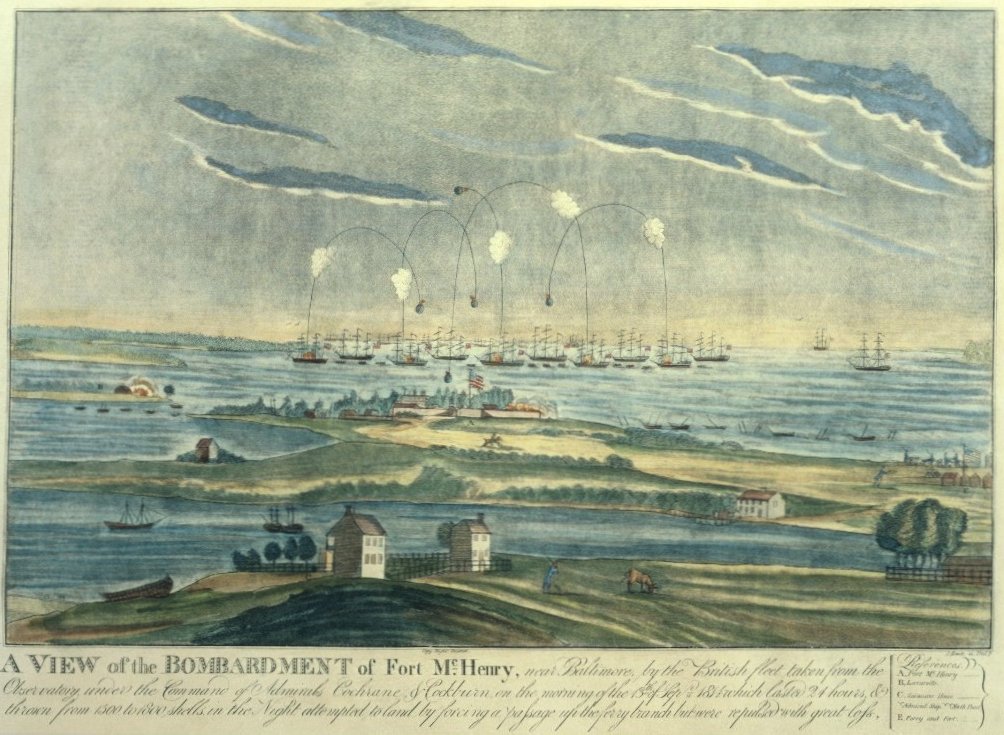

Britain’s main preoccupation at the time was a world war against Napoleon, then reaching its climax in Europe, with the Emperor soon in full retreat from Moscow. Enormous financial and military resources were being poured into that conflict, with a naval blockade of all French ports; and a British army under Wellington in the Peninsular, slowly pushing north to the Spanish border and southern France. For these reasons, plus the huge logistical challenge of getting troops, supplies and ships across the Atlantic to support operations in North America, the War of 1812 began, for the British, on something of a shoestring. But as more resources became available in 1814, British forces began offensive amphibious operations, including the assault on Washington and the increasing blockade of the American coast. In fact, through one of life’s little ironies, those campaigns helped create two icons of American patriotism. The torching of Washington DC so badly scorched the Presidential mansion that they had to paint it white to hide the damage: hence the White House. And it was British bombs bursting in air over Baltimore’s Fort McHenry that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the “Star Spangled Banner”.

The war ended by treaty rather than the outright defeat of one of the belligerents, and there was no territorial loss or gain. So while clear winners or losers may be hard to pick, some lessons were learned. First, for the Canadas, that they could successfully defend their territory if necessary: the key step to nation statehood. They could look to the future with confidence and conviction. Next, the United States learned the limits to its then power, and while it would continue to expand on its continent, it would be to the south and west. The War, and the successful British blockade of New England in particular, may also have made the young Republic more determined to be self-reliant, and so contributed to laying the foundation for its formidable manufacturing industry. Britain learned that while it might briefly have been able to throttle a nascent United States, there were reserves of muscle and potential there that commanded respect.

What we all learned over time was more important: that as allies and partners, Canada, Britain and the US could together create centuries of mutual peace and prosperity. That is a lesson worth remembering.

Update: As part of a War of 1812 exhibition at the Canadian War Museum, the High Commissioner filmed a short video on the British perspective of the War of 1812:

Hello, I love the history, thank you very much for the post … I never imagined as truly crossed Canada.

greetings

Interesting perspective. I think if you ask an American educated person, they would state that the US ‘won’ the War of 1812, yet here in Canada we were taught that Canada won. It is the subject of great discussion with my American friends. I tend to believe that it was US expansion policy that led to the invasion of what is now Canada, yet our residents, British forces & most important to our success in the battles, our First Nations led to the ultimate defeat of the American goal…afterall if governance of all of North America was their goal, they were unsuccessful, hence Canada/Britain was victorious. As a proud Canadian & strong monarchist, I look forward to celebrating one of our early military successes & defining moments in our path to nationhood!